NOTE BY THE INTERVIEWER: This first question came out of a preliminary discussion that occurred prior to this actual interview. I had pointed out that I had learned from an article I was writing on the Hermann Hauser family of luthiers, that a woman (Kathrin Hauser, daughter of Hermann Hauser III) had finally appeared in what I perceived to be a male dominated world of guitar builders. Ervin had also pointed out that, while there are few women in this field, and few Asians, there is to his knowledge only one person of African-American or Afro-European descent who can be found making guitars in either Europe or the United States. It is truly a field that is mostly dominated by white males, and blue-collar guys at that. Ervin was of course referring to the network of people who build acoustic guitars and/or other instruments by hand. With these things in mind, I asked:

PB: How do you fit into this world of American guitar lutherie?

ES: I fit in a bit anomalously. But I feel very comfortable here.

Let me give you some context first. The genesis of American guitar making culture has roots in the centuries-long crafts traditions brought over from Europe that pertain to making things by hand. This was in fact the universal custom before the Industrial Revolution. Many of the people who wound up gravitating towards this work on these shores (America) were from the trades — in other words blue collar & working-class people — and it’s continued to be that.

European trained labor had been organized around the Guild system, so that if one wanted to do a particular kind of work they’d enter a Guild and be trained, tested and approved. That Guild system was already falling apart by the time this continent was being populated, and the Guilds were getting even fewer entrants as Europeans emigrated in droves to the new land. And then the Industrial Revolution really pushed the Guilds into obsolescence; who needed a trained work force when machinery would do the job so much faster?

So, when Europeans came to this country and started to figure out how to make a living they not only didn’t have Guilds or master teachers or anything like that, but they also didn’t feel they needed them. They had whatever education, skill, talent or ambition they had; they could pick up a trade without needing to be trained for ten years; the field was wide open for them to get minimal to adequate training somewhere, rent a space, hire some workers, tell them what to do, and they’d have some kind of a production shop without all the folderol of years of training and tradition. Or, alternately, one sub-contracted and became an organizer of other people’s labor and products, manufactured under one’s own label. That was the business model. And it produced a bumper crop mix of entrepreneurs, charlatans, talent, con men, business geniuses, failures, successes, semi-competents, outright predators, catch-as-catch-cans, and honest guys doing the best that they could. In terms of skills and talents, that was America’s real melting pot.

For these reasons, as far as my own work is concerned, the American model has since its inception and until my generation been: “You want a guitar? The Martin, Gibson, Taylor, Gretsch, or Guild Company will be happy to make it for you”. Such factories dominated the production horizon until my generation, at which time individuals began to come forth and enter the work.

At least, they did so from the 1930s on. Before then, a lot of what relatively few guitars were being made in this country were being made by Italian and other immigrant craftsmen — often for a company that would sell it under its own label. In the 1930s, though, with the advent of the Singing Cowboy movies (do any of you remember Roy Rogers, Gene Autry, etc.?); those movies brought the guitar to the fore in a way that had not happened before . . . and the factories were off and running. It helped enormously, too, that these cowboys were playing Guilds and Martins, etc.

But that was in the 1930s and 1940s; that kind of entertainment had been needed by a population that had been hit hard by the Depression. Eventually, things changed. I think that a significant reason for young, single, skinny males from my generation thinking that they could do this kind of work was the general culture of permissiveness — which itself was an outgrowth of the significant fact that this was the first generation of Americans (i.e., the post-war generation) that was economically secure. Previous generations had had to scramble for a living. Life was uncertain. There had been, as I mentioned, the Great Depression; there had also been wars, life on the prairie, competition and struggle on every level of urban life, etc. . . . so we young fellows of my generation were very privileged and we felt safe enough to do this oddball thing, because we knew if it failed our parents would take us in and support us. And, in those days — the 1950s — it wasn’t hard to find a job doing something, at least among Caucasians. There wasn’t the problem of unemployment such as exists today. There was general prosperity.

It was in that crucible, I think, that the impetus to take up hand tools and make guitars first arose. As far as I know there had been only a few (one Spanish, one Puerto Rican, and a relatively few Portuguese and Italian) transplants who had been making classical guitars in this country since the 1940s. There may have been one or two more that I haven’t heard about. And these were the first actual seeds of American lutherie. But the soil for such a crop, if I can put it like that, was poor. The first time most Americans ever heard a guitar by itself, without accompanying instruments that were being played simultaneously, was around 1953 when they saw and heard Elvis Presley gyrating around and strumming his guitar.

You may remember that popular and non-orchestral “music” in the 1920s, 1930s and 1940s was big bands . . . or smaller bands . . . of various kinds; and certainly not individual singer-players). Then, in the 1960s when the Folk/Ethnic Music movement made the guitar even more popular, young Americans began to get interested in making this all-of-a-sudden-user-friendly instrument. These factors had all fertilized the soil that the seeds of American lutherie could grow in. And the first seedlings were white.

[NOTE: This is not quite accurate. As I mentioned above, European immigrants who came to these shores brought traditional skills of all kinds with them, and the Italian immigrants in particular had brought traditional mandolin, violin, and guitar-making skills with them. Accordingly, most of what counted as stringed-instrument-making work that was done in the United States in the 1800s was being done by Italian craftsmen. And although most of these are forgotten about today, in their own day they were it. Not least, they were white. Even now, when there are guitar makers in just about every American town and city — at least amateur ones — I can only name one Afro-American person who is making (or probably even repairing!) acoustic guitars. There are otherwise Italians, Japanese, East-coasters, West-coasters, Midwesterners, Southerners, New Englanders, both Western and Eastern European imports, and even a few women! The same was true of the Crafts movement that started in the 1970s and concerned itself with the making of wooden, ceramic, glass, clothing, quilting, etc. objects, and that has kept on going . . . and whose members are still light-skinned but very largely grey-haired now.]

Interestingly, the Folk Music movement itself was rooted in the earlier work of people like Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, the Lomaxes, and the Delta bluesmen whose earlier recordings were now being paid attention to. None of these had previously been on the radar of any mass audiences. And for myself: when, at the age of about ten, I got thrilled by listening to Elvis Presley wail out the words to “Hound Dog” while flailing away on his guitar, it was utterly beyond my imagination to suspect that I’d wind up making my life around the making of that kind of instrument.

A second significant factor in early American lutherie was that a lot of us were oddballs and nonconformists (the conformists, organizers, and business-minded came later). Interestingly enough, most of this first generation played flamenco guitar, not classical; there seems to be something about how the brain is organized so that if one gets interested in playing flamenco guitars it’s easy to segue into making them. Equally interestingly, classical guitar players often go into computer work when it’s time to move on. In any event, the free spirits who began to do this work quickly found a challenge in obtaining information: there weren’t any teachers around to get help from. There were no books, no magazines, no lutherie schools, no Internet. And the market for handmade instruments was small. So, it was really hard to find a way to survive. In fact many didn’t survive; they dropped out and/or went off and got some other work.

Now, I need to make two important points. First: as I stated, most of the first generation of American luthiers got their start by tinkering with the making of nylon string guitars, not steel string ones. [NOTE: there were a few exceptions to this trend: Roy Noble, Mark Whitebook, Don Brosnac, David Russell Young, John D’Angelico, and the earlier Orville Gibson, C. F. Martin, and the Larson brothers come to mind — and D’Angelico, who became the most successful of any of these as a luthier, was busy inventing a different kind of steel string guitar – but then again, he represented a continuation of the Italian immigrant craftsman that I’d mentioned above.] But any general interest in making steel string guitars came second even though this is the modern American guitar.

Why is this? Well, it had always been possible to accept the idea of a handmade classical guitar. They were all made like that in Europe, weren’t they? That tradition already existed. However, it was very difficult for the same legend to attach to a steel string guitar . . . until there were [non-Italian-and-a few-other-European-and-Eastern-European] Americans [such as early Romanian-American guitar maker Bozo Padunavac] who were engaged in hand making of at least some kinds of guitars. As I said, the making of “American” guitars had been, from the beginning of “the American way of doing things”, the realm of factory work . . . and there was a learning curve for the general public if it was going to wean itself from its focus on commercially made products.

The second reason is connected to the first. Necessarily, none of the early steel string guitar makers who were attracted to this work gave any thought to making “better guitars” — in the professional and artisanal sense that exists today. Those concepts didn’t exist yet. And there was no market for such even if that idea had existed. Instead, these first steel string guitar luthiers largely sought to gain a foothold by offering things that the factories couldn’t provide: custom width fretboards, different-than-standard scale lengths, personalized inlays, guitars with a cutaway or other ergonomic features, non-standard woods, unusual numbers of strings, or just the novelty of having a guitar made by someone you knew. Otherwise, these luthiers were happy to make guitars that were as good as the Martins, Gibsons, etc. But, principally, they were going for the in-between-the-cracks market with an artisanal spin. The phenomenon of aspiring to produce steel string guitars that were actually better and more desirable only began in the 1970s. I’ll say more about this a bit further on. As far as the guitar market was concerned, I might mention that until the mid 1970s guitar stores were reluctant to even take hand made guitars on consignment: they would take up space that would preferably have been given to a Martin or a Gibson, which would sell more easily: those guitars had name recognition value . . . and our hand-made ones didn’t.

I mentioned that I’m somewhat anomalous. I never seemed to have been interested in setting up any kind of a production regimen or shop. So, a lot of my guitars are one-of-a-kind. They’re often artistic. I’m happy with that. It keeps the work from becoming stale.

I’m anomalous also in that I have had more formal schooling than a lot of my peers and professional colleagues have had. That’s largely because I’m European, I’ve traveled a lot, and because my parents gave me a sense that education is paramount. They stuck me in schools as soon as we got to any new country or town. I spent what seemed like several centuries in schools, colleges, and universities. I practically learned to crawl and walk in school hallways rather than at home, and English is not my first language. I’ve read a lot, I’m articulate, and I’ve even taught at the University level . . . all before I made my first guitar. I learned how to talk to professors, how to write papers, and how to sound like a professor . . . and all that’s mainly from just having had a ridiculous amount of formal education. None of these things have to do with anything like being smarter than anyone else, but rather with the fact that I am comfortable with teaching; that work makes sense to me. Most guitar makers are happy to just do the work. I do the work but also write about the work and teach a lot.

And mostly I guess I’ve always tried to be me and follow my instincts, instead of trying to copy what everyone else was doing. If I’m anomalous, it’s because of these things.

PB: My next question comes in response to your list of “what the guitar is about”. I quote from your blog:

“The guitar is about many things: craftsmanship, commerce, history, tradition, entertainment, science, wood and gut and a few other materials, physics, acoustics, skill, artistry in design and ornamentation, music, marketing and merchandising, magic, etc. Mostly, though, the guitar is supposed to be about sound. But that thing is the hardest of all the things on this list to pin down and get a measure of.”

In listening to and viewing your guitars, there are clearly two distinct ways you appreciate your work. They are about art, and they are about sound. Which comes first?

ES: Well, left to my own devices, I’ve always liked to keep my hands busy…crafts projects, models, whittling, gluing things together, etc. So, there is a significant sense of occupying myself with such play — to make something nice, unique, and that is hopefully really cool or neat. There seems to be a primary and quite likely selfish element of creativity in my approach to things.

From the standpoint of economic survival, there are two ways to go — or at least two easily identifiable positions on a spectrum. First: make your guitar be identifiably different from the competition’s in some way; make it in quantity; and then advertise and market it to death. Second: make fewer guitars that sound or function better in some way. The latter is for me the easier of the two roads to navigate, and I’ve been fortunate here. I don’t think I could organize myself to produce a larger number of the same guitar. It would be the opposite for someone like Bob Taylor, I think; for him the first option would be the default choice; the second would be difficult.

I mentioned that the quest for “a better steel string guitar” — or at least a steel string guitar that could hold its own against the commercially made ones — began in the 1970s. I was one of the pioneers in that. In the mid-1970s I began doing work for some of the serious guitar players who happened to be recording on the Windham Hill Label. That label wanted to make recordings and pressings that were on a par, in quality, with recorded orchestral sound quality. That effort became the point at which new demands were made on the steel string guitar. Musicians had begun to find that (1) the available guitars really didn’t play in tune. Well, they never had and they never had really needed to. And (2) the Windham Hill people needed guitars that would record evenly. This has to do with the fact that most guitars’ sound needs to be “equalized” in the recording studio because they are so inconsistent in how they radiate sound off their surfaces; most of them project sound unevenly in different directions. It is the job of the recording engineer to place microphones where they’ll pick up the best sound, and to boost and repress frequencies that the guitars produce unevenly in any event, so as to produce recordings that tonally homogeneous. Part of this is also because microphones hear things differently than the human ear does, and a guitar that might sound good to you or me could sound shockingly bad when recorded . . . or vice-versa.

It was noticed by the Windham Hill recording engineers that when these musicians played with a guitar that I’d made or modified, their work became much easier. That was the start. All in all, my relationship with the Windham Hill label gave my work a significant boost and direction. I’ve written more fully about that in my books and various articles and essays.

PB: What do you attribute this to? How did you come to solve these problems?

ES: I think that I can identify several factors in this. I can attribute a lot of it to the fact that I had started out by making Spanish guitars, not steel string guitars.

That effort brought me into contact with the classical guitar playing and making networks, whose adherents have comparatively sophisticated standards. Guitar makers in that field approach the instrument in a more disciplined and comprehensive way than steel string makers had been taught or trained to do. Part of this lay in the fact that luthiers in that network felt that they were emulating the work of actual guitar making masters who bore Spanish and German names; steel string guitar makers were emulating factory guitars that had romantic (and commercially advertised) cachet attached to them . . . but these are essentially quite different motives and goals. All in all, I think it would be accurate to say that, among steel string guitars makers, no meaningful training existed in those days at all beyond (1) following the blueprints, and (2) clean assembly procedures during construction.

I’m not putting anyone down in saying these things, by the way; I am describing two different starting points as accurately as I can. Another way to look at this is that classical guitar makers and players since the time Andres Segovia brought that guitar to the world’s concert halls have needed to pay attention to sound and its nuances; these are the things that give life and color to the music that is at the center of such work. But the steel string guitar has had no such champion. Really, who comes to mind as a pioneer in early steel string guitar sound? Elvis Presley? Peter, Paul, and Mary? Bob Dylan? Jimmie Rodgers? Woody Guthrie? Pete Seeger? The Kingston Trio? Leadbelly? You see: it’s not the same.

In any event, in my own way, and because of that initial exposure to the classical guitar world, I more or less knew about the importance of paying attention to elements of construction that may have seemed minor, but that might well be important . . . even though I didn’t understand what any of that meant at first. Those people who bought a book to learn how to make steel string guitars wouldn’t have been exposed to that. For them, building guitars has very largely been a recipe approach:

- You take this wood

- You take it down to this thickness/size/shape

- You glue these pieces of wood together

- Sand it all smooth and apply a finish to it

- …and, presto! You have a guitar

PB: That whole side of the problem-solving that you experienced through working with the classical guitarists, having to please these high-profile performers: was this missing, or did they [steel string builders] simply not have the exposure to such feedback?

ES: Mostly, I don’t think that steel string guitar makers had access to critical feedback. It’s a bit complicated, but this is an interesting question that I’d like to amplify on.

Early on, when I was making only nylon string guitars, young classical guitar players would come to my workshop and play my latest instrument, and then ask if they could borrow it to show to their teachers! Well, no, I wasn’t going to let the guitar out of the place without it being paid for. It took me several of these experiences to understand that these people weren’t trying to be dishonest or weird: they genuinely needed their teachers’ opinion and okay about a guitar because, as students, they did not feel entitled to any definite opinions; or perhaps I should say that they did not trust their own opinions fully, and they preferred to defer to their teachers. There were “right” answers and “not so right” answers. Steel string guitars players, in contrast, were more direct and did not feel the need to have their opinions reinforced or validated: they would tell me right then and there whether they liked or did not like an instrument . . . and I found that directness refreshing.

While it may be enough in the steel string guitar world that one likes (or does not like) a particular guitar, I discovered early on that there is more to a classic guitar’s sound than just that. I went to a professional classical guitar player’s home once to show him my latest guitar. He sat down with it and played some music on it, and then he got out his own guitar and played the same passage on it. The end of that piece consisted of a musical resolution in the form of two chords, in which the final one resolved the sense of “winding down” of the next-to-the-last one . . . and so put that passage of music to rest. The man pointed out that, on his guitar, those two final chords sounded different. And they did sound different in character, in the feel of them.

It’s difficult to describe this in words, but take my word for it that the difference was clear. Then, he pointed out that those same two chords played on my guitar didn’t sound different; they had the same quality, depth, warmth, sensibility, auditory value, or coloring, depending on which words one prefers to use. But the sameness of tonal character was obvious. Played on this man’s own guitar the sound worked better, musically, for winding down the story that the music was telling. More specifically, something was audibly being resolved, completed, and put to bed at that point in the music; and it was a richer auditory experience to have the change of chordal character able to follow and express the shift, in that piece, of the winding down of that musical narrative. I heard the change in the sensibility of the two chords follow the change of feeling in the ending of the music.

My guitar, in comparison, simply played the same two final chords without sounding emotionally different; they replicated the chords/notes that were on the printed music, but didn’t correspond to changes in the story line that the music was carrying. I learned something that afternoon that I hadn’t understood previously: that better guitars have many voices, or at least tones of voice. My guitar had only one. Put technically, my guitar had limited dynamic range: the player could coax only a limited tonal spectrum out of it; he could obviously, with his own mastery of technique, coax more variety of sound from his own better guitar.

No steel string guitar player until Daniel Hecht came along (he was one of the Windham Hill guitar players, whom I’ve written about separately) had ever talked to me like that, or played a passage of music differently in different parts to illustrate the musical ideas that he was trying to express. Daniel had had formal training, which explained his sophistication of ear, mind, and word. And I found that feedback on that level was much more useful than any other I’d received up until that point. It got me to think . . . or at least start to think.

For myself, I didn’t know what I was doing in the early years of my lutherie. Most of my guitars weren’t all that good, to be honest. I first noticed the importance of paying attention and learning through my experiences at the Carmel Classic Guitar Festival of 1977, which I’ll describe later on, and from having personal experiences such as the ones I just described. These had an overriding musical significance that I did not understand in the beginning. But mainly, in those early ears, steel string guitar players didn’t really need guitars that would do this or that specific tonal thing; they needed guitars that they liked . . . perhaps without being able to say why.

I was doing a lot of repair work in those days, which brought in the bulk of my income. I had started meeting steel string guitar players through doing repair and setup work for them. I must say that doing repair work provided me with an important education such as the younger crowd does not get these days: it is a window into what fails in guitars, and what does not, and maybe even why. Anyway, these musicians were perfectly nice people and, in due time, I began to make steel string guitars.

PB: Assuming of course, that each instrument has its own distinct personality, what consistent elements do you try to include that make your guitar a “Somogyi”?

ES: Besides being an object of beauty, the guitar has, for me, primarily been a sound producer. I think that is because I’ve played flamenco guitar since high school. The main difference between a guitar and this table [points to his kitchen table] is that the guitar is constructed so as to produce sound, whereas we don’t rely on a table to do that. But a fuller answer to your question would be a continuation of the things I’ve been saying.

Let me say that in terms of the physics and acoustics, sound is nothing more than excited air molecules hitting our eardrums. The greater number of air molecules and the greater extent to which they are excited, and the frequency or frequencies at which they are excited gives us various sensations of tone and sound, volume, projection, warmth, brightness, and so on. Accordingly, the guitar is something that I think of as being an air pump. If it excites a little air, that translates to a little bit of sound. If it excites a lot of air, then, you get a lot of sound. The strings supply a limited energy budget. You can play violins all day long until your arm falls off and they’ll keep on producing sound. But with the guitar the instant the strings stop, so does the sound. [Here, Somogyi is referring to the fact that the sound on the violin continues as long as the bow is continually drawn across the string, while on the guitar, from the moment the string is plucked, the note starts to die away]. So, there is a limited amount of energy to drive the guitar, and the job of people on my end of it [the builders] is to see how much of that our guitars can capture dynamically and how much of that can be used to excite air. Therefore, if we can think of the guitar as being an air pump whose job it is to excite a lot of air, with a fixed energy budget, then you can start to think about how would one go about making such a device.

In Spanish [meaning classical and flamenco] guitar making, there is an adage to the effect that the best guitars are the ones that are built on the cusp of disaster. There’s nothing comparable to this in the steel string guitar making canon. A principal idea behind the Spanish guitar is to make it as lightly as one dares, but without going past the point of there being structural failure. So you want to find the balance point where that pull of strings and their torque are just withstood by the system. The strings’ energy then will go into and through the system and give you the desired end result, which is a lot of sound. On the other hand steel string guitar makers build their instruments very sturdily. Part of this has to do with the identity of the steel string guitar as a folk instrument that travels easily and gets a lot of wear and tear from handling; it’s a valued but not quite so revered an object. As far as the ability of a guitar to take in and use its strings’ energies goes, overbuilding a vibrating system holds it back from vibrating. And in the case of both classical and steel string guitars anyone who is paying attention will build as lightly and just strongly enough as they can. (At this point Somogyi leaves the room, then returns with four items in his hand: a small local phone book, two plywood boards, a cardboard rectangle, and a Japanese fan.)

This is one way that I have of illustrating the concept of the guitar as an air pump, to my classes. Each of these objects can be used to move air. [He tries to fan himself with the phone book]. There’s a certain energy required for my wrist and my hand to move this clunky object. But the phone book is flopping around and it’s really not very effective as an air pump. I mean, given how much work I’m doing here, clearly, this is not the best arrangement.

[Somogyi picks up the thicker of the two plywood boards. It is stiffer than the phone book used].

A better arrangement would be this: fanning myself with a board that is as stiff and heavy. This does a better job of moving air, [he fans himself with the board]. Now, it’s a little clunky because this thing has a lot of mass and inertia and it takes quite a bit of effort over the long run for this part of my hand to hang on to this and to move it. If there were limited energy budget, I could only do this a limited number of times before my hand got tired; the energy would be gone; and in the case of the guitar once the energy is used up you have to strum the strings again. Still, you get more bang for the buck, air-movement-wise, than you do with a floppy and unresponsive structure.

Since the energy budget must be factored in to these examples, a better fan would be a board that requires less energy to move. [Somogyi picks up the thinner of the two plywood boards. It is still stiffer than the phone book]. This one moves more air with less effort: a step in the right direction (Fig. 1).

[Somogyi picks up the cardboard rectangle. It is stiffer than the phone book used, but just barely]. One can try to fan one’s self with something very light weight, like a piece of cardboard . . . but it can only be flapped around with so much energy before it folds over (Fig. 2). So if we want to move some air around efficiently then we are looking for something that doesn’t weigh much but that is rigid enough when driven by the appropriate load to push some air around.

Let me take a brief detour into the realm of engineering, which has to do with the study of structures. Everything man-made is constructed so as to hold up and is crafted — either consciously or intuitively — with principles of structural engineering in mind: buildings, bicycles, chairs, boats, pots and pans, cars, electrical towers, bridges, etc. Everything. If there’s any concern in that thinking so as to enable these structures to move or flex around (vibrate) without falling apart then, as I just mentioned, you are going to be thinking about the stiffness or strength-to-weight ratios of the materials, and a certain flex in the design. If you can use fewer materials and make it sturdy enough to hold up, it’ll be cheaper; and if the material has some flex in it, it can vibrate/oscillate too.

How does one achieve these things? Well, let’s look at the room we’re sitting in. It is made up of joined-together truss elements, joists, studs, beams, rafters, etc. As a matter of fact it is precisely this internal structure that is doing all the heavy lifting, as it were. Whatever skin is on the outside is mostly decorative and minimally structural. In structural engineering terms, it’s usually what is on the inside that is holding a thing up against the forces of gravity and use.

However, there is another branch of engineering called monocoque engineering. Most people have never heard of it. But that’s the study of structures and constructs in which there are no or minimal internal structural elements in the traditional sense of the word. Rather, it is the skin that holds it together.

PB: I never heard that word, can you please spell that for me?

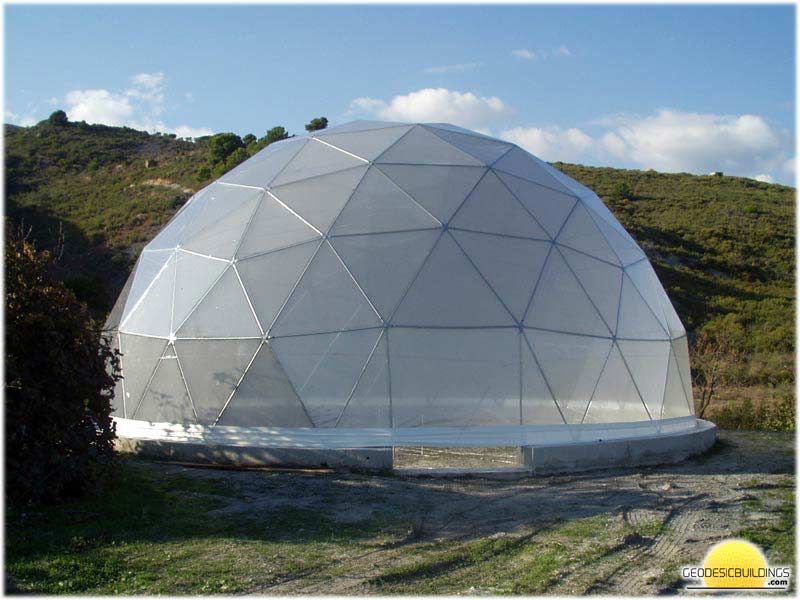

ES: [Ever the comedian, Somogyi replies] Sure! S . . . K . . . I . . . N. . . ! [Laughter] One example of a monocoque a cardboard box, which is really very strong for something that has so little weight. You can stand on some cardboard boxes without crushing them. Eggs are monocoques too, as are lutes. So are those very lightweight airplanes that are made out of a few internal trusses and covered by Mylar or some lightweight skin. Canoes are monocoques. It’s their skins/shells that are 80% of the structure. Ditto geodesic and architectural domes. The ideal is to have a construct comprising of a delicate membrane held together mostly by itself, with as few internal structural elements as possible . . . that is yet strong enough to hold up under the various forces and stresses that it will be subject to. I think of the best guitars as being monocoques which function as air pumps.

So, these (holds the pieces of plywood in his hands) represent the way in which most factory guitars are made. They are tough and durable, and seriously overbuilt. (He picks up the Japanese fan, opens it up and fans himself.) This is also a monocoque: a lightweight membrane that is reinforced by the arrangement of its own configuration, and with otherwise minimal supports. This is exactly what a properly made guitar is (Fig. 3). It takes very little effort for me to fan air with it. Now, if I were to hook this particular monocoque up to a 5-horsepower motor, it would be torn apart. But that’s not required in this case. The only thing that is required of this is that it be connected to my wrist and activated by it.

I try to make my guitars be like fans, in this sense: a membrane reinforced by minimal and judiciously arranged bracing (that’s another, separate issue: the placement of the reinforcing elements can be critical). We can go one step further, too, in regards to allowing the membrane to be its own support and be free of the need for secondary reinforcing elements: curve the membrane so as to stiffen and strengthen it. Frisbees and paper plates are excellent examples of this (Figs. 4a, b, c). So are archtop guitars, violins, geodesic domes, etc. These are true monocoques in that they feature membranes that do not need supports (i.e., bracing) in order to hold up. In the case of the guitar, energy-wise, the strings are the equivalent of my benevolent wrist: they determine the motive force. To the extent that you can pare back on unnecessary structure and mass you will observe a simultaneous increase of tonal response — in any guitar (Fig. 5). In a nutshell, that’s what I try to do that makes my guitars different.

PB: You are quite informed about these principles of engineering, yes?

ES: Well, I’ve had a lot of practical education supplemented by having learned some engineering jargon. This is all engineering 101 material, you know. All engineers know this. But guitar makers aren’t engineers; they’re blue collar guys who like to use their hands and work with wood. They mostly haven’t had the perspective that knowing such principles can bring to the work. They are very largely making copies of copies of copies of overbuilt guitars, and thinking that that is the proper way for them to be made.

PB: Do you have one (of your guitars) that I could play and listen to today?

ES: I think I have one, if you want to plunk on it.

PB: That would be an honor. [I play a series of E chords up the neck. I can notice right away the incredible balance between the strings, and then hear the “bloom”, a sound quality that Somogyi has worked on and written about for many years, which for me occurred in the upper positions (7th to 9th fret). The sound, quite noticeably, seemed to get stronger before its normal decay. Being a classical guitarist, I played some Bach and a lyrical piece by Stanley Myers, known as “Cavatina”. Once again, the separation of the melody from the chords was clear and distinct. I mentioned how easy it was to play in the upper positions, even without a cutaway]. Can you comment on some of the details on this guitar?

ES: [Commenting on heel design.] I know that you’ve seen lots of guitars. One feature of this one is the very small heel; it doesn’t get in the way of the hand moving up the neck to play the higher notes. The heel of a typical steel string guitar is bulky; the curve from the neck to the heel is almost always a 4-inch diameter circle. This is because the front roller of every belt sander on the planet is 4 inches in diameter and that tool is used to shape that feature of the modern guitar. It’s not in the tradition of manufacturers to invest time in handwork and hand tools. My guitar heels are all carved by hand, and the small-radius curve is an ergonomically more intelligent arrangement for the left hand. Even if you don’t have a cutaway, that will let you get your hand higher up there [points to the higher frets]

[Ervin comments on the abalone inlay in the fretboard] This is green abalone; it gives a nice little sparkle. This rosette is something I came up with. You won’t find this on the average steel string guitar because their soundhole inlays are traditionally very plain. I call this the sunset rosette. Rather than being geometric or linear it’s just shadings of color. I think it’s very nice (Fig. 6).

PB: It seems to go along with what we discussed earlier about the more natural flow of lines rather than having it look like it was just machined in there. That is really beautiful.

ES: Thank you. [Commenting on the bridge:] That was my attempt at an art deco look. It takes more work than the average bridge, which is usually quickly and efficiently made. It doesn’t do anything that other bridges don’t do, but it’s got some detailing and it has character.

PB: Let me put a question to you assuming the role of a prospective customer. If I were to order a custom guitar from you I would tell you things about the guitar that appeal to me. For instance, I like the sound of a cedar top for steel strings but I like the sound that I get from spruce when I am using nylon strings. Can you build me a guitar that has those qualities?

ES: When clients approach me, they are often looking for something. They have some reason for looking for something better, or more exciting, or newer than what they are already playing on. I ask questions such as: “what would you like?”, “what do you like and not like on your present guitar?”, “what do you think would work better?”, and “would you like something like [this or that]?” It’s like cooking food. I try to figure out what are they after. And, if it makes sense to me, and if I think I could produce that, then I will.

Most people want the same thing, although they don’t quite know how to say it. Aside from whatever words and phrases you could bring up to describe this thing, they want something that they could sit down with, strum, and say, “Oh my God!” That’s what they want…something that gets their attention and that they can spend time exploring pleasurably.

PB: From my point of view, when I put my fingers on the strings [of the Somogyi guitar], it was as though there was no effort at all needed to produce the sound. It almost felt as though I was playing a harpsichord where you just touch the key and there’s the note! There was no effort.

ES: That’s another level to making guitars. One thing that clients sometimes tell me is something along the lines of, “you know, I’ve had my guitar for a long time but I sit down to play it and after thirty minutes my left hand hurts.” So we start looking at the contouring and the size of the neck, and the action, and match these to the player’s hand. These are ergonomic considerations. They involve the musculature of the hand, and how it is used. If the guitar is not comfortable to play, that’s a legitimate reason to figure out what can we do about that.

Now, sometimes I can tell someone that they don’t need a new guitar, but maybe they need to have the neck worked on instead so it’s comfortable for them, or perhaps the strings need to be at a different width of spread. People come in all different sizes, but commercially guitars usually don’t.

I mentioned that did repair work for many years. Most young guitar makers have never had more than a very little repair experience. They know how to assemble a guitar but they don’t know much about how guitars are built and what fails. And they don’t yet understand that both guitars and their players can mature and, like some couples, grow apart. I have had a good handful of people over the years call me up and say, “Look, I’ve had this guitar for four years. It’s not playing in tune anymore. I think the tuners are slipping. I might need you to replace the tuners.” They would bring the guitar over. The tuners were fine, the nut and saddle were fine, and the frets and strings were all good. But their ear had improved! Now they could hear that the guitar could not play in tune, and they simply could never hear that before. You have to meet people where they are.

PB: That’s the thing. Guitar players come to you having only played factory guitars, maybe a few hand-made guitars, and they don’t understand what is actually happening to the instrument. For me also, I have played a lot of steel string instruments and yours is not like any of those that I have played. The moment I picked it up I could tell. The balance between the weight of the neck and the body is so correct, so balanced. It doesn’t feel like the neck is going to go this way [angling the neck to the floor] or that the body feels so cumbersome.

ES: X-Brand guitars: a free helium-filled balloon with each sale, to hold the neck up!

PB: Can you tell us of any new and/or surprising discoveries that you made after completing one of your instruments? What can you tell me about one of them?

ES: There are a number of things I can mention. My current favorite is the out-of-sync metronomes experiment. Do you know about this? Somebody filmed this phenomenon and put it on YouTube, and you can find it by Google-ing “metronomes in sync”. It’s really a hoot to watch this. The screen shows thirty-two metronomes on a table. They have all been set to the same oscillatory speed, but they are all initially stopped. Then two hands appear and jiggle all of them into motion in a random way. Almost immediately all the metronomes are waving their cursors around, WAY out of sync with each other. It’s like a classroom full of kids who are raising their hands and trying to get the teachers attention. Chaos! But very soon the metronomes are all in lockstep!

How is this possible? It turns out that if the table or surface that those metronomes are on is stable and solid, they will continue to be out of sync forever. And why wouldn’t they? They were started out of sync with each other and are not expected to vary in speed. But if that table or surface is not rock solid and has a bit of yield or movement to it, then the metronomes can modulate one another. What that means is that they can borrow energy from and lend energy to their neighbors . . . so that after about 2 ½ minutes, all of them are perfectly in lock step. It’s utterly amazing. If you pay attention you can see some of the metronomes actually speed up or slow down in order to catch up with their neighbors. After a while they are all in lock step just like a well-trained army platoon on a parade ground.

What this has to do with guitars is that if a particular one is built to a certain threshold of . . . uh . . . well . . . flimsiness, it then stops being and acting stiff, clunky and massive. I mean: all guitars will make sound; but if you make their parts flimsy enough then you notice that some really interesting things can happen; one of them is that, like the metronomes finding each other’s speed all by themselves, the guitar can get louder all by itself! Normally, when you strum a chord, that sound comes out of the guitar at “maximum” volume and then it attenuates, until it eventually disappears. The sound at the beginning comes out as strongly as it’s going to be, like horses coming out of a starting gate, and then drops off.

But certain guitars that are lightly enough built are responsive in a different way. They have parts, sections and components that can modulate one another. When you strum on such a guitar the sound of course comes out immediately; but then, after a perceptible amount of time, the sound gets louder. More correctly, the sound is louder in the sense that it becomes more full. You’d think this is completely bizarre because you haven’t hit the strings again. So, what is going on that the guitar is now being louder than when you first strummed the strings?

Well, what’s happening is that the parts, sections and wood fibers of the top and back are lining up with each other and working more in sync — just as the metronomes did. The various parts and quadrants of the guitar top “lend”, “borrow”, and “exchange” energy with their neighbors. It takes them maybe half a second or a second for them to stand in line and march as a column, as it were. This can be understood in terms of impedance, which is another engineering concept, and which specifically happens to come from the realm of electrical engineering. Do you know what that is, impedance?

PB: [At this point I was feeling like I was in an episode of Science Friday on National Public Radio!] Is it resistance in the wires?

ES: Yes, it’s a resistance to transmission of energy from one material into another, or through the same material, or one form of energy into another, or some combination of these. If there is, for instance, electrical energy in some tool or device that one is using, that same electrical energy may be converted to mechanical energy, or kinetic energy, or light energy, or sound energy, or magnetic energy, or thermal energy. The electrical energy of the drill is delivered in the form of torque energy to whatever material one is drilling into. Once it arrives at the material, that energy is converted into mechanical/excavational energy (i.e., the disruption of the fibers or structure of that material as it is being perforated), plus sound, plus heat: the drill, the wood, and the drill bit all get warmer. If there had been no sound energy radiated off, they would have gotten warmer still.

Now, to the extent that there is a mismatch of ability to transmit, receive, or convert the energy, there is impedance. Impedance causes loss — perhaps through inefficiency, damping, siphoning off some energy into a non-useful direction, just plain old resistance in the form of insulation of some type, etc. — and you get less output than there was input. In the case of drilling a hole into wood or metal, some of that energy will have gone into simply making the tool’s parts work; and some of that energy will have gone into heating the tool, the drill bit, and the material. Some of it will have gone into making a lot of noise. And depending on the material and what the drill bit is made of there may also be a bit of conversion into magnetic energy, and/or causing sparks. But in any case, there is that much less hole drilled, for reason of those losses. That is an example of impedance.

In the guitar, the impedance that occurs between the energy impulse of the strings and then the amount of air that is actually and finally excited so as to become sound, takes several forms. Mainly, kinetic string energy is shunted off into damping (the materials simply absorb the energy), mechanical motion (which uses up a certain amount of energy to friction and consequent creation of internal heat), and poor couplings (mechanical failure to transmit all the energy across the junction; for instance, you will waste a lot of the drill’s energy if you don’t push it into the material with enough force). The main difference in these examples is that while you don’t need your electrical drill to make noise, you do want the guitar strings’ kinetic energy to become as much noise as possible.

In fact, the drill example can be used to illustrate the problem of overbuilding or underbuilding, in guitar making. Hardly any guitars are underbuilt: they’d fall apart sooner or later. But plenty of guitars are overbuilt. The drill won’t get much work done if it is not pushed into the material you’re trying to put holes into. But if you push too hard (for the drill’s capacity to penetrate a given material) then the drill will slow down and eventually grind to a halt. If a guitar were built in a way analogous to that, it would make much, much less sound. You have to match incoming energy with result . . . and that’s what making guitars correctly is all about.

Also, all guitars fight their strings to some extent simply by having mass: mass has inertia and it takes energy to make something move. If the guitar is too heavily built then its materials will simply not receive the string energies and these cannot unload their kinetic energy into the guitar. An extreme example of this would be to hook your guitar strings to two anvils; they will receive/soak up virtually no string energy at all; it will stay in the string until friction with the air and its own inertia stop it.

All I’ve done is simply to have noticed this. Now, I’m not the first to have noticed this, and I certainly didn’t invent the phenomenon. The Spanish makers whom I so admire weren’t academically or scientifically trained, but they paid attention! They listened to the sounds of their guitars, and to the feedback from guitarists who played them, and they noticed something from things like “that last guitar was better than this other one. What did you do?” Not being distracted by computers, Wikipedia, or books, the Spanish guitar makers simply noticed things that were right in front of them. And not being distracted by computers, Wikipedia, or books, they had time to think.

So: the surprise that you asked about was that I noticed that my guitars got louder when I strummed them. More specifically, I noticed that my guitar’s sound blooms after I strike the strings. And that was completely unexpected at first. (Somogyi writes extensively about the “bloom” in sound both in his book and on his blog.) It didn’t seem to be my doing. It was something the guitar was doing. And this brings us back to what the metronomes were doing: holding hands and walking together, working together. Well, it’s right there in front of you, in the metronome experiment. And it’s just as surprising to hear it in a guitar as to see it with metronomes.

PB: What is different about each of the models you make?

ES: If you were a guitar player in Spain you’d go to your local friendly guitar maker and say, “I want a guitar”. And everybody knew what that meant, because Spanish guitars are pretty much all the same size and shape. But in this country, because of the competitive pressures of life, industrial powers have needed to produce consumer goods for a growing and very mobile population. Guitar manufacturers came up with different versions of the guitar that were marketed for different purposes, to various niche markets, and at different specific price points. That was not needed in Europe, but it was very useful here.

The first guitars were small. In time, people wanted LOUDER guitars. The nature of popular entertainment changed. It grew hugely. If you weren’t working, then music was the way to be entertained and to meet people. You hung around and played, or danced, or listened. This was particularly true before TV, movies, or computers.

Metal strings came on the scene around the 1880s; that was a big boost, because you could get more sound. This itself came about largely through advances in wire making technology when this country was expanding westward and they needed wire for fences, etc. Therefore, society came up with the method for making a lot of wire. They put some of the wires on guitars and this material lasted longer than gut strings, was cheaper, made more noise…everybody was happy.

One of the entertainment modes that existed was the orchestra. There were, accordingly, guitar orchestras, mandolin and mandocello orchestras, violin orchestras, balalaika orchestras…you name it! The guitar model that was assigned the function of playing in the orchestra was, imaginatively enough, the Orchestra Model, or what we now call the OM. The dreadnaught was bigger bodied and it put out a lot of bass, which worked for a lot of popular music.

Altogether, for a long time, the guitar did not have its own strong identity. It was, by itself, a more or less anonymous member of a group of instruments that played as part of an ensemble, usually with mandolin, banjo and fiddle, and maybe some other things. Even in jazz the guitar is only part of an orchestra.

The guitar only began to have its own distinct voice in the 1950’s, when Elvis Presley was on TV and first exposed a lot of people to the sound of one guitar alone. It actually was the first time that many people just heard a guitar. I am talking here about a mass audience watching televised entertainment, rather than the audience that might have been in a real audience at an actual musical performance. A decade later the folk music movement drove the guitar and its sound much deeper into the popular consciousness.

PB: So it seems to me that the different models, or styles of guitar arose out of need and/or usefulness. Was it the players or the manufacturers who determine which models needed to be produced?

ES: The accepted models are mostly set by the Martin and the Gibson Companies. Everybody knows them, and everybody copied them — until people like me came along. Also, historically, even though various “models” had been prototyped or made in small quantities, the principal manufacturers never undertook making any kind of guitar in large quantities until they were sure that enough market demand for these existed so as to make the venture profitable. Some of our most popular and familiar models of steel string guitars were not made in large quantities until twenty years after they had made their initial appearance.

In my opinion, most steel string guitar makers are not well trained, nor do they have broad knowledge. They make guitars, but don’t think that they understand that most of them are making copies of copies of copies, etc., of the originals, and that there has been very little variation or diversification in them. The Dreadnought is the most popular. I have made Dreadnoughts, although I don’t get much call for them any more. The Dreadnaught is THE most popular shape of steel string guitars today. I make something I like better that I call the Modified Dreadnaught. I was probably the first one to make something like that, and this was before alternative names for models got to be popular.

I took the shape of the Dreadnought and re-designed/shaped it for Daniel Hecht, whom I mentioned to you, and who wanted something that worked better ergonomically. I called it the Modified Dreadnought; that doesn’t sound very imaginative, but I simply didn’t know what else to call it. Now, if you look in guitar magazines, everybody who makes guitars has some romantic proprietary name attached to their models. “The Sequoia”, “The Grand Teton”, “The Empire” model, “The Golden Cuspidor!!” [laughs] It’s become quite an industry — which is another difference between steel string guitar making culture and European guitar making culture. In the European culture, for anybody who works as an individual luthier, it’s unthinkable to not put one’s own name on his or her instruments. In this country the attitude is: “Who knows my name? I’m going to call it something that sounds GREAT!” Thus the guitars are just as often called something iconic or geographic, or associated with a city or the great outdoors, as they are called after people.

PB: What is your Modified Dreadnought all about?

ES: The Dreadnought is a big blobby guitar; at least, it seems so to me. The classical guitar has some very nice curves. The Dreadnought . . . well, not so much. It’s just big, and its shape is not . . . well . . . interesting. Its musical uses were for group performances of people who stood while they played, with a strap around their shoulders to hold the guitar up. The instrument’s physical balance was never important. When you sit down to play it, it slides around your lap; the waist is shallow; it’s a little top heavy. It’s simply not made for playing while sitting in the way the classical guitar is. So, the Modified Dreadnought is the Dreadnought re-shaped, not re-sized. It has a more pronounced waist and a higher center of gravity so it’s not top-heavy. You can sit it and play it comfortably on the lap.

Within my lifetime, guitar fingerpickers have come to the fore. These are people who play the guitar in a sitting position. They need an instrument that works with those ergonomics: that’s the Modified Dreadnought, in fact. I listened to what my client wanted and I came up with something that made him happy. I believe I was the first one to modify the Dreadnought.

[The following question is the one that seemed to give Somogyi the most trouble. He clearly possesses a rational and analytical mind. To wrap his head around a topic such as what might have been, a somewhat speculative question, took a succession of three more emails before he, and I, felt it was adequately answered.]

PB: My next question is also drawn from something I read in your blog. It concerns your visit to Woodstock and the remarks you made about the culture and style of East Coast/New York guitar builders who mostly specialized in arch-tops rather than flat-tops, etc. I found this very interesting. I want to ask you how do you think your career as a builder might have been different had you started out in New York rather than in the San Francisco/Oakland area?

ES: Well, we could talk about Chaos Theory. That is a relatively new concept. To my understanding, this is the mode of thought that recognizes that one thing follows another in unpredictable ways. You just can’t know what impact something you would have done has had, or whether it has any impact or effect other than the one you intended, or where on the planet, or to what extent. And for me to consider, for me to imagine that I might have been had I lived back East rather than on the West coast, and to try and imagine how my life would have developed . . . well . . . I can’t do it. One’s week, let alone one’s month or one’s year or one’s decade is made up of so many things that are way outside the level of consciousness or awareness. I mean, just to be facetious, let me say that if I had crossed the intersection of 42nd and Grove, in Oakland, on April 12, 1964, I might have been hit by a truck. That wouldn’t have happened had I been in New York.

PB: [Laughing] I am sorry my question came off as way too broad. I was thinking more specifically about sound and how perhaps building archtop guitars might have affected the way you thought about sound.

ES: I’ll tell you something that is significant. I started out making guitars in the early 1970’s as a hobby — until I got a real job, I thought. As it turned out I never was able to find a real job.

PB: Lucky for us!

ES: I’m still chewing on the question of how my life would have developed differently had I been located on the East coast. But a lot of life’s successes and failures come about through context and being in the right place at the right time. Period. Well, I’m going to tell you about three things that happened that were unexpected but that influenced me fully as much as the 35,689,917 things that might have happened to me had I been living back east would have.

I’ll start with some context first, though. When I began making my first guitar in 1970 I was more or less a hippie — that is, a bearded (but clean-smelling) young man who was living without much sense of direction. I was living in the Bay Area largely because I’d graduated from U.C. Berkeley, and it was “home” to me. I embarked on that first guitar making project casually; as far as I knew it was going to be a hobby-project to tide me over until I got a steady job.

I didn’t know any American guitar makers in those days; I had not even heard of anyone outside of Spain or Germany to be making guitars by hand. Still, I’d spent a Summer in Spain and hung out around some of the guitar shops in Granada; and later, when I went to grad school in Wisconsin in the late sixties I met a man, Art Brauner, who had built a guitar with the help of Irving Sloane’s pioneering book Classic Guitar Making. I was impressed; having been a student much more than anything else in my young life I’d not produced much of anything other than lecture notes, papers, essays, reports, and test results — but this fellow had made a real object! An actual guitar! It made an impression, in spite of the fact that doing this kind of woodworking was an odd way indeed to spend one’s time in those days; no one in my family had ever puttered with hobbies, done woodwork in the basement, welded, built models from kits, made furniture or anything like that; they were too busy surviving and simply didn’t have the time to. Anyway, I eventually completed my first guitar — a classical model — using Sloane’s seminal book. I think all of us young American guitar makers used that book to get off the ground: American lutherie culture was in its very early stages.

Having made that first guitar brought me a bit of repair work from friends, and this represented a bit of welcome income — so I opened up a small guitar repair shop on Grove Street (which later became Martin Luther King Avenue) in Berkeley, California. This was in 1971. One year later I took over retiring guitar maker Denis Grace’s larger shop in Oakland, and for a long time made my living principally by doing all kinds of stringed instrument repairs. It’s amazing that I survived, because I had no training, no experience, no knowledge, few tools, no teachers, no work discipline, no professional standards, and only marginal skills. Still, I survived, and made a few guitars each year. Because I played flamenco I was making mostly Spanish (classic and flamenco) guitars, as well as lutes and dulcimers; if nothing else, I wasn’t afraid of tackling different projects. I also made a few steel string instruments that, in reality, were nothing other than bigger Spanish guitars with metal strings. Well . . . I didn’t know any better. I did feel more or less pleased to think of myself as a luthier, though; I think the romance of it kept me going.

It most certainly wasn’t the income; I remember that I grossed $1800 the first year, $2500 the second, and $3500 the third; this was from 1972 through 1974 (I had a part-time job teaching, on the side, to help me pay my bills). It helped that I was young and single and living simply. But I didn’t really face up to how inadequate and amateurish my work was until 1977. In that year I was invited to display my guitars at the Carmel Classic Guitar Festival. I was to be one of seven luthier exhibitors.

The Carmel Classic Guitar Festival is the first of the important factors I mentioned above. I’d built a handful of guitars by 1977 and felt happy to be invited to show my work. I can tell you that while my parents could not begin to fathom what I was doing making guitars when I could have had such a promising career doing something reasonable, my friends had been unfailingly supportive and encouraging to me in my guitar making efforts. (Guess which set of people I put my faith in?) In any event, I went to Carmel feeling a little cocky and smug, thinking to impress the people there just as I had wowed my friends.

Carmel is an upscale vacation community four hours’ drive from San Francisco; there’s no reason to go there outside of visiting art galleries and restaurants, to play golf, breathe clean seaside air, and relax. The guitar festival itself — the first one I’d ever gone to — was a prestigious event that drew important people from all over this country and even a few from overseas. It had been organized by Guy Horn, a prominent local classical guitar teacher. I will remain forever indebted to him for reasons that I will go into below. Among my fellow exhibitors were Jeffrey Elliott, Lester DeVoe, Randy Angella, and John Mello — all of whom went on to support themselves by making Spanish guitars.

The festival was a horrible experience for me. My work, in its full and splendidly careless amateurishness, was the worst of anyone’s there. Worse yet, this was clearly revealed to everybody. The three-day long event was a humiliating and sobering experience that I came back from feeling severely shaken and depressed. My friends had, in fact, been no help to me at all with their uncritical kindness and I hadn’t learned anything from it. I confronted the fact that I had been more or less wasting my time living out a hippie fantasy. It calmly stared right back at me.

Understandably, I experienced a crisis. It became clear to me that I had two choices: quit making guitars and do something else, or buckle down and do better work; the experience of the Carmel festival was decisive and made any denial or rationalization impossible. It took me several weeks of re-evaluating to realize that I actually liked making guitars enough to stick with it, and that the path was open to me if I wanted to apply myself and do professional-level work. That was my real starting point as a guitar maker. And it was within a year of that decision to do the best work I could, and not let things slide, that I started to make steel string guitars. Miraculously, the timing worked out: I was starting to meet serious steel string guitar players in that period — and specifically the first of my Windham Hill contacts.

The second factor was that the timing of all this was fortuitous in a much larger sense: that was when making [hopefully better] guitars was beginning to make a blip on the cultural radar. The folk/rock movement of the sixties and seventies had certainly sparked the playing of guitars; but all the famous folk, country, bluegrass, and popular singers, duets, and groups (such as Peter, Paul and Mary, the Mamas and the Papas, the Kingston trio, the Beatles, Bob Dylan, the Weavers, Dave van Ronk, Johnny Cash, Elvis Presley, Simon and Garfunkel, Roy Orbison, Ricky Nelson, Buddy Holly, the Limelighters, the Everly Brothers, Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Kate Wolf, the New Christy Minstrels, Phil Ochs, Ian and Sylvia, Joan Baez, etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. etc. etc.) were using store-bought factory-made guitars, not handmade ones. These were, by the way, all steel string instruments; the only guitarists who were using handcrafted instruments at that time were the nylon and gut string group: the classical and flamenco players. It is true that the Martin Company made a nylon string guitar, but it was just as fully a mass-produced product as their other guitars were, and it was mediocre as a guitar. I was tempted to just say “very mediocre”, but that’s redundant. Anyway, handcrafted steel string guitars were only about to make an appearance . . . via the Windham Hill label. That Windham Hill door, it turned out, was one of the most important ones that had or would ever open up for me. And none of that would have happened without my disgraceful showing at the Carmel Classic Guitar Festival.

I should explain my reference to Windham Hill a bit. That recording company introduced solo steel string guitar music to the public. Windham Hill’s impact on this specific music, and contemporary guitar music on the American and world scene in general, was phenomenal. The guitarists who recorded on that label became leading points of musical inspiration and reference for many young guitarists, both compositionally and acoustically — in part because, for the first time, the guitar was being recorded and listened to at the level of fidelity of sound previously occupied by classical music alone, and in part because no one before them had composed interesting and complex music for the steel string guitar alone [NOTE: This isn’t 100% true, but it’s close. The very first strains of melodic and solo guitar music (as opposed to its being an accompanying instrument) came from John Fahey, Leo Kottke, Clarence White, and Doc Watson. They were pioneers and inventors; they just weren’t mass market successes in the way that Windham Hill was.] And this acceptance of better-quality guitar music also became my point of entry into the world of serious lutherie. I was lucky to have met the Windham Hill guitarists when the Windham Hill phenomenon was just getting off the ground. That was the point in time when factory made guitars were showing their limitations and guitarists were for the first time needing genuinely better instruments: guitars that played in tune, that had good sound and dynamic range, and that recorded well.

I was lucky to be living an hour from Palo Alto, which was the epicenter of that musical ferment. It helped that I’d figured some things out about guitars by then; I’d had six years of experience which I finally began to pay serious attention to after my disappointing showing at the Carmel Festival, and my instruments were by then finally good enough that people could consider playing and buying them. Happily, my steel string guitars performed well not only acoustically but also did exceptionally well in the recording studio; the players very much appreciated being able to make better recordings; and my word-of-mouth reputation grew. But none of this — other than the incidental fact of my living an hour away from a group of talented steel string guitar musicians — would have happened had I made a good showing at the Carmel Classic Guitar Festival. I would probably have continued to make classical guitars and my life would have gone off in a very different direction.

If you remember, I had mentioned three influences. The third one was that I met a woman whom I married, which relationship enabled me to continue to make guitars at my own pace without worrying about surviving: she was bringing in the bulk of the income. If that piece hadn’t been in place, then I might have needed to decide — for expediency’s and survival’s sake — that I was going to make one model only, bet my future on that effort, and not waste any time by experimenting with design variables.

As it happened, it wasn’t a happy marriage at all. If it had been, then I might have had many children and my life would have been full of that, instead of my work.

Well, everybody has stories like these and these are just three of mine. How does one evaluate the importance of that kind of matrix? I have no clue. These just happen to be significant influences of my life experience.

Let’s segue into something that has also been influential. This is that my family’s agenda for me was that I go to medical school and be a doctor. I almost did. I came very close to that but something unexpected happened at the last minute that made me think that maybe I didn’t want to do that. But if that hadn’t happened, I would have continued on in my original direction. In retrospect, I don’t know if I would have become a good doctor, a bad doctor, a happy doctor, a doctor working in some corporate place, or a hospital, or Doctors Without Borders — or even a doctor at all, in spite of having tried. I just don’t know. But I don’t think we’d be having this conversation.

[PB: And from a later email, Somogyi continues on this point in answer to my original question]

ES: I often find myself thinking from a wider perspective than the original question or proposition had been. My mind works like that. And for that reason, hypothetical questions such as “how do I think my life would have been different if I’d lived in New York rather than in the Bay Area” are nothing more than invitations to fantasize about what might have been. I cannot truly know, but I can imagine many possibilities; how impossible would it have been for me to have wound up running a whorehouse in Singapore, for instance? Stranger things have happened, as Somerset Maugham described brilliantly in his short stories.

In any event, the guitar scene itself was an important real-life factor in how my life has developed. I play flamenco guitar. This would have brought me into contact with nylon string guitar players, and eventually steel string folk and bluegrass guitar players. The East coast is famously more the natural habitat of the archtop guitar, which I’ve never really become interested in. There’s less of that on the West coast. I might have found my way to making archtop guitars had I been living in New York, but I don’t know how much energy and focus I could have mustered behind that effort, as I genuinely don’t connect with them.

I do expect that there’s a fairly healthy acoustic guitar scene on the East Coast, and there certainly would have been the Greenwich Village music scene going on in New York. I am fairly confident that I would have been attracted to that. There’s probably even a good classical guitar and flamenco network, and I may well have been pulled into that world.

I am thinking that this question is somewhat along the lines of an intellectual exercise for you. You may have read my autobiographical chapter [in my book] by now and become aware of the fact that I am a Holocaust survivor. There were numerous instances in that history in which had circumstances been a little bit different I would have been killed. It was, as a matter of fact, the national policy of the country of my birth at that time that, because of the accidental fact of my father’s having been born into a family that practiced Judaism, we be exterminated. To be blunt, I’m not alive for lack of anyone’s trying. Finally, there was a war going on at the same time, which mandated that there’d be uncounted random civilian deaths in any event.

So, you see, I’m not really set up to mentally follow out hypothetical threads that have any great logic or linearity to them. That kind of thing works on certain levels, of course, but my own life has been such that I’m more amazed at the roller-coaster ride than by the skill and foresight of my personal brain cells and protoplasm. I think the river that one has fallen into is at least as significant as the log one is hanging onto.

Also, the question of what I would have become focuses on the things I do for a living, not on what I might have become internally, as a person. I am actually more interested in this than I am about income-producing behaviors. I became who I am, internally, in terms of my sense of self (that is, as opposed to my job description) that came from from a series of what anyone in their right minds would consider accidental meetings. And a lot of competent psychotherapy, I might add. I bow to the forces of life for having allowed me to be in the right place at the right time in these instances. They saved my soul. I have NO idea how I would have been able to negotiate such journeys had I been living in another city with another culture. Really. The sheer randomness of life as I have seen it is beyond words.

On the other hand, there’s a concept in psychology called “over-determination”. This refers to the eventual recognition, when one has looked at a structure or a personality or a character long enough, that whatever happened could not have happened in any other way or along another line or in another direction: it was over-determined and everything pointed to that, whatever it is or was. All the gravity and motives pulled in that direction. This utterly applies to my life, in spite of what I just said about randomness being no less true. But you’d have to know more about me to understand how true this is. From that point of view I probably would have become what I am now, but with quite possibly quite a different spin, on the East coast.

Well, that’s it for now. Did I mention that my brain likes to take the overview route?

PB: There is a feeling I get from you, one of wanting to “give back”, to other guitar builders and to your students, for example. It comes across to me, for example, in your book, “The Responsive Guitar”, where you included photos of other people’s work. [in fact, the book opens with 22 pages of photos of other people’s guitars that Somogyi admires, followed by a smaller number of beautiful photos of the details found in Somogyi’s instruments]. Also at an earlier point in your life you were heading for medical school, which would have benefited people in a different way from how your life and work has benefited people through your art.

ES: Well, not quite. My parents . . . well, I was brought up in a very authoritarian household. We never discussed anything. My father issued orders. So, it was irrelevant whether I might have wanted to do this [going to medical school] or whether I was even interested in doing that. I WAS going to do that! So I probably wasn’t thinking of being helpful to people. I mean: this was my portfolio; this was the job description that was quite literally handed to me. And, I don’t know what I would have made out of that. I probably would not have become some kind of money-grubbing businessman who wore a medical gown . . . but I don’t know. I instead became the kind of money-grubbing man I am now.

PB: [Pushing the point that there were inklings of a generous, altruistic spirit lurking about I pressed on with my point.] You went into the Peace Corps, for gosh sake! That’s the point I’m making. [Re: the Peace Corps; Ervin was in South America, in Peru; it was a really good experience for him that broadened him enormously.]

ES: That was afterwards. It was largely because I didn’t want to get drafted for the Vietnam War. This was in 1965. My derailing of my medical career occurred in 1964. Like everything else that’s significant, it’s really complicated. You know, there’s a Jewish adage that I like a lot: “if you want to make God laugh, tell him your plans”.