PART 3 OF 4 (Part 1, Part 2, Part 4)

by Ervin Somogyi

This is the third installment of an article on the historical development, the present state of, and anticipated future changes in guitar design and guitar making. In both earlier installments I outlined this path by examining the historical development of both the classical and the steel string guitar.

As I pointed out previously, design of classical guitars is very largely internally driven. That is, by the needs of its music. Classical guitarmakers are trying to make tools for musicians who are focused on qualities of sound such as sustain, separation, dynamics, clarity, projection, evenness, balance, richness and timbre — all of which provide a palette of tone with which the music can be expressed and through which the music sounds better, more complex and more interesting. The classical musician’s concern with nuances of tone and voicing have not applied to the steel string guitar until recently. Music for this instrument has primarily been amplified and/or accompaniment, and has served to show off composition, style, rhythm, accompaniment skills, percussion (Michael Hedges started a whole new industry of such playing style), and also effects and volume. But there has not been a need for an acoustic sound which can stand on its own merits and which enhances and expresses tonal qualities of musicality, as there has been for the classical guitar. Design in steel string (as well as electric) guitars has been externally driven, by commercial producers of guitars and electronics and all their marketing — as well as by the needs of the greater musical performance culture of folk, Celtic/Irish, blues, jazz, bluegrass, R & B, gospel, country, rock, ethnic, rock and roll, New Age, fusion and popular music.

I think predictions about the future must take these root influences into account. However, since there are two main influences or traditions out of which guitars are made today (factory and craftsman), there will likely be two sets of answers to the question about what the future will bring. Or three, to the extent that there’s overlap. Let me explain what I mean.

In the first of these articles I described the trajectory of growth of American lutherie over the past thirty years. Concurrently, there has also been a spectacular explosion of factory production. In my professional lifetime the names of Breedlove, Taylor, Larrivee, Bourgeois, Rainsong, Collings, Ovation, Goodall, Fox, Godin, Gurian, Mossman, Santa Cruz, Gallagher, Dean, Tacoma, etc. and a host of electric guitar brands such as Alembic have been added to the earlier established commercial producers — and that’s just in the U.S. and Canada. This list will doubtless grow.

By the rules and logic of operating at a factory or commercial level and surviving in that competitive business one has to think, plan, implement and advertise changes and improvements of the product in terms of (1) use of advanced technologies such as computer-operated tooling, (2) use of improved-yet-cheaper, alternative, and space-age materials, including things like ultraviolet-cured finishes, (3) introduction of variety and new, heretofore unavailable, models, (4) streamlined and more efficient methods of production, (5) improvements in quality, (6) celebrity endorsements, and (7) higher per-dollar value, presented to the consumer’s attention through continually changing and increasingly sophisticated advertising. There is a truth and a logic in these things, and they will underlie much of what the guitar playing public will be exposed to, and buy, in the future. Because I see these as being very much the wave of the future for commercially made guitars, I’d like to say more about several of them.

By the rules and logic of operating at a factory or commercial level and surviving in that competitive business one has to think, plan, implement and advertise changes and improvements of the product in terms of (1) use of advanced technologies such as computer-operated tooling, (2) use of improved-yet-cheaper, alternative, and space-age materials, including things like ultraviolet-cured finishes, (3) introduction of variety and new, heretofore unavailable, models, (4) streamlined and more efficient methods of production, (5) improvements in quality, (6) celebrity endorsements, and (7) higher per-dollar value, presented to the consumer’s attention through continually changing and increasingly sophisticated advertising. There is a truth and a logic in these things, and they will underlie much of what the guitar playing public will be exposed to, and buy, in the future. Because I see these as being very much the wave of the future for commercially made guitars, I’d like to say more about several of them.

Advances in Efficiency and Technology

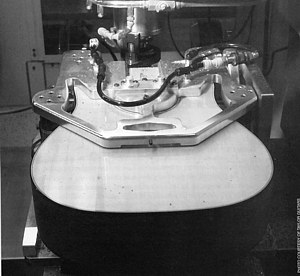

Factory production of guitars has become amazingly sophisticated, compared to how such work was done only twenty years ago, and is likely to continue on this course. Most notably, the changes are in the area of technical supermechanization and computerization in the service of efficiency and productivity. Parts are now routinely cut and shaped by computer-guided tooling, and human labor is increasingly limited to asssembly of parts, administrative support (office work, recordkeeping, accounting and billing, supply requisitioning, R & D, payroll, marketing and management), training, subcontracting, and tool maintenance — exactly as in any automobile assembly line. Subcontracting has grown to be an important part of all factory production, which is increasingly becoming a forum for the speedy assembly of components made by someone else and, increasingly, this someone else is in a foreign country where labor costs are low. Vacuum clamping has revolutionized the holding of parts as they are shaped and glued and has speeded up these processes dramatically, and new fast-drying glues made specifically for industrial production speed these processes along even further. New ultraviolet-cure finishes involve new technology coupled with the use of a new material, and have the advantage of allowing a guitar to be completely finished in around four hours, compared with days or weeks for the same results to be achieved with lacquers or urethanes. Electronics are continually improving and we have more and better ones to choose from than ever before. Guitarmaking at all levels has shifted from use of more or less trained and skilled labor into reliance on a general and institutionalized infrastructure of jigs, forms, molds and fixtures, the purpose of which is to insure error-proof repetitive operations by relatively unskilled workers.

The reliance on the new computer-operated tooling is daunting and dazzling to those who don’t work at that level. Insofar as its purpose is to eliminate as much as possible of the human factor in the production of identical parts, it is entirely logical to assume that one of the next steps will be to eliminate, as much as possible, the human component in the assembly operations. This is being done now robotically in the automobile-making and electronics industries. As commercial guitarmaking involves many of the same repetitive operations as any other manufacturing process has, there is no reason whatsoever to think that some form of robotics won’t be brought into guitarmaking as soon as it is feasible. The use of computers in record-keeping, inventorying, billing, designing and prototyping, desktop admaking and marketing, etc, — unknown twenty years ago — is now so commonplace as to be entirely unremarkable and even essential. Everyone has computers, beepers, faxes, cellular phones, modems, call-waiting, etc.

New and alternative materials

After technological advances, the next big item in the picture of changing commercial production is the growing reliance on new materials, finishes (already mentioned), adhesives and processes. Use of plastics and synthetics is steadily on the rise, starting in the l970s with Ovation’s space-age synthetic cast-body design, Adamas’ aluminum necks, phenolic resin fingerboards, increasing use of epoxy-graphite neck reinforcements, etc, etc, and currently ending in Rainsong’s graphite instrumens and Martin’s recent release of a guitar made out of high quality formica. Bet your boxers that we’ll see more of this kind of thing in the future. New quick-curing wood glues, cyanoacrylates and epoxies are now used commonly because of their obvious savings in time. The Breedlove guitar company has committed itself to using various plentifully available and sustainable yield domestic woods as an alternative to the traditional but rapidly disappearing rosewoods and other exotics; and their guitars are being found to sound good. Amplification systems are continually evolving and improving and have resulted in the steadily growing culture of acoustic-electric instruments: to list the newest equipment alone would probably fill up at least a page of text. The larger factories such as Taylor, Collings and Larrivee have switched to the new ultraviolet-cure urethanes; these are much easier to apply than other finishes, look good, and increase both productivity and profitability. And as soon as this technology becomes more easily affordable, smaller factories can be expected to follow suit.

After technological advances, the next big item in the picture of changing commercial production is the growing reliance on new materials, finishes (already mentioned), adhesives and processes. Use of plastics and synthetics is steadily on the rise, starting in the l970s with Ovation’s space-age synthetic cast-body design, Adamas’ aluminum necks, phenolic resin fingerboards, increasing use of epoxy-graphite neck reinforcements, etc, etc, and currently ending in Rainsong’s graphite instrumens and Martin’s recent release of a guitar made out of high quality formica. Bet your boxers that we’ll see more of this kind of thing in the future. New quick-curing wood glues, cyanoacrylates and epoxies are now used commonly because of their obvious savings in time. The Breedlove guitar company has committed itself to using various plentifully available and sustainable yield domestic woods as an alternative to the traditional but rapidly disappearing rosewoods and other exotics; and their guitars are being found to sound good. Amplification systems are continually evolving and improving and have resulted in the steadily growing culture of acoustic-electric instruments: to list the newest equipment alone would probably fill up at least a page of text. The larger factories such as Taylor, Collings and Larrivee have switched to the new ultraviolet-cure urethanes; these are much easier to apply than other finishes, look good, and increase both productivity and profitability. And as soon as this technology becomes more easily affordable, smaller factories can be expected to follow suit.

Production of New Models

Commercial enterprises must produce new products continually. They are in the business of making mass-produced products for a mass market, and the mass market requires newness and differentness. Accordingly, new models appear regularly as old ones fade from popularity and/or new market niches are identified to be exploited. Thus we have the ongoing parade of small guitars, large guitars, entirely new models, re-issues of previous guitars, anniversary and commemorative issues, travel guitars, blue/green/red guitars, student guitars, collector’s editions and presentation models, use of materials in new combinations, electronics, features, etc., etc. Variety sells.

Improved Quality

It’s natural and logical to ask how all these things improve the quality of the final product. Making something faster sounds postive; but one might equally ask what is the advantage of making a plastic guitar more quickly, outside of the bottom line. This doesn’t seem like an unreasonable question. One should understand that the notion of quality in manufactured products is different than the notion of quality in individually made products. According to a guitar industry spokesman at a recent trade symposium, quality, from a factory point of view, is the same as replicability of components and efficiency of assembly. That is, the factory man considers quality to be the measure of how efficiently his parts can be identically made and how fast his instruments can be assembled in a consistent and trouble free manner. I’m not making this up: this is how the language is used. Some elements of design and assembly may in fact result in improvements in structure and response in a guitar, but these are incidental to the streamlining of the production operations. In fact, all the elements of the future of commercial production which I’ve been describing have more to do with the conditions of production than with the end product. I repeat: for commercial producers Quality = Efficiency of Assembly Process. If you trouble to peruse the professional and trade literature you will find that no other criterion is ever mentioned.

It’s natural and logical to ask how all these things improve the quality of the final product. Making something faster sounds postive; but one might equally ask what is the advantage of making a plastic guitar more quickly, outside of the bottom line. This doesn’t seem like an unreasonable question. One should understand that the notion of quality in manufactured products is different than the notion of quality in individually made products. According to a guitar industry spokesman at a recent trade symposium, quality, from a factory point of view, is the same as replicability of components and efficiency of assembly. That is, the factory man considers quality to be the measure of how efficiently his parts can be identically made and how fast his instruments can be assembled in a consistent and trouble free manner. I’m not making this up: this is how the language is used. Some elements of design and assembly may in fact result in improvements in structure and response in a guitar, but these are incidental to the streamlining of the production operations. In fact, all the elements of the future of commercial production which I’ve been describing have more to do with the conditions of production than with the end product. I repeat: for commercial producers Quality = Efficiency of Assembly Process. If you trouble to peruse the professional and trade literature you will find that no other criterion is ever mentioned.

However, from the end user or musician’s point of view quality has nothing to do with any of this: it has to do with how playable a guitar is and how good it sounds. This also is, normally, the attitude of the small scale maker, for whom efficiency is important but secondary to his concern for creating a personal and effective tool for the musician. While the main ideal behind factory guitars is that they be made quickly, strong and salable, the highest ideal behind the handmade instrument is quality of sound, playability, and craftsmanship — even if the craftsman is inexperienced and falls short of this goal. These concerns, and how they are likely to play out in the future within the context of competition with factory made products such as those described above, will be the topic of the next, and final, installment of this series.

(reprinted from Fingerstyle Guitar, #42, 2001)