PART 1 OF 4 (Part 2, Part 3, Part 4)

by Ervin Somogyi

This is the first of a four part series on the state of contemporary American guitarmaking. I intend to sketch out the general landscape of how the guitar developed historically, what it is now, and, lastly, what shape I think it is likely to take in the future. As I am a professional luthier, I’m going to tell this story from my hands-on perspective. It’ll be a nice change from the editorial voice of commercial/music/factory industry, which already gets a lot of copy space. This is just as well, in my opinion, because the story of American lutherie is well worth knowing.

This is the first of a four part series on the state of contemporary American guitarmaking. I intend to sketch out the general landscape of how the guitar developed historically, what it is now, and, lastly, what shape I think it is likely to take in the future. As I am a professional luthier, I’m going to tell this story from my hands-on perspective. It’ll be a nice change from the editorial voice of commercial/music/factory industry, which already gets a lot of copy space. This is just as well, in my opinion, because the story of American lutherie is well worth knowing.

When I began building guitars thirty years ago there were very few independent guitarmakers around. Those few who had gravitated to this work were generally creative, not able or willing to work within the mainstream system, and personally rather eccentric. Borrowing or stealing what little guitarmaking lore had leaked over from Europe, virtually all of these early builders made classical and flamenco instruments in the “old fashioned” way — with carpentry tools. The mainstream system, as far as guitarmaking was concerned, consisted of American factories such as Martin, Gibson, Harmony, Guild, Gretsch, and Fender. Such Japanese and Taiwanese guitar factories as existed were turning out ornamental crap, and the only real luthiers anyone had ever heard of — like Ramirez, Torres, Orville Gibson, Santos Hernandez, C.F. Martin, Simplicio, Hauser, the Larson brothers and D’Angelico — were all long dead. This was not a lutherie environment rich in promise. Those very first independent guys really had a hard time fitting in, and they paid a high price for being trailblazers. Not a few of them fell by the wayside into craziness or simply disappeared, unable to make a living at lutherie. Their legacy to us is that they formed a nucleus of interest and possibility for newcomers who also wanted to work wood with their hands, to create something that had beauty and gave pleasure, and to have a life which offered a different flavor of meaning than that of American pop culture. We, who came later, owe them a lot.

American guitarmaking has come a long way since those early days by several measurable standards. First, a generation of American musical instrument makers has preserved, refined and extended an originally European tradition of woodworking which had lain moribund with disuse in this country, and made it viable. Second, whereas thirty years ago a luthier was mostly an object of curiosity and an anachronism, handmade lutherie (whether you are making two guitars a year or forty) is now a more or less familiar and accepted part of the American landscape. Consequently it is now more possible for a luthier to make, if not a living, at least some money at it. Third, the guitars which are being produced now are, on the average, much better than the average instrument produced then. Fourth, a generation of instrument makers has evolved which is not made up so much of hardcore mavericks, but rather of established professionals and intelligent amateurs who take their work seriously and with a great deal of justifiable pride. Fifth, an entire (and continually growing) body of literature and have been created by this group, where there were none at all before. Sixth, this general growth of interest in musical instrument construction has created the conditions which have made possible the rise of two national luthiers’ organizations; furthermore, these not only provide active forums for free exchange of information to anyone who has interest in this craft, but are in fact the leading sources of information for young instrument makers overseas. And, lastly, we have created the first generation of American luthiers who are considered world class. Not bad, for a bunch of guys who started out as self-taught hippies.

American guitarmaking has come a long way since those early days by several measurable standards. First, a generation of American musical instrument makers has preserved, refined and extended an originally European tradition of woodworking which had lain moribund with disuse in this country, and made it viable. Second, whereas thirty years ago a luthier was mostly an object of curiosity and an anachronism, handmade lutherie (whether you are making two guitars a year or forty) is now a more or less familiar and accepted part of the American landscape. Consequently it is now more possible for a luthier to make, if not a living, at least some money at it. Third, the guitars which are being produced now are, on the average, much better than the average instrument produced then. Fourth, a generation of instrument makers has evolved which is not made up so much of hardcore mavericks, but rather of established professionals and intelligent amateurs who take their work seriously and with a great deal of justifiable pride. Fifth, an entire (and continually growing) body of literature and have been created by this group, where there were none at all before. Sixth, this general growth of interest in musical instrument construction has created the conditions which have made possible the rise of two national luthiers’ organizations; furthermore, these not only provide active forums for free exchange of information to anyone who has interest in this craft, but are in fact the leading sources of information for young instrument makers overseas. And, lastly, we have created the first generation of American luthiers who are considered world class. Not bad, for a bunch of guys who started out as self-taught hippies.

In this time, factory production has changed dramatically as well. While lutherie has grown from the romantic passion of the slow, carefully working amateur and enthusiast to the serious business of making a living — with all the jigging, tooling up, scheduling and paper/office work this requires — factory production has become almost unrecognizable in its investment into technology and large scale, high-speed and automated production. The use of new and synthetic materials has become common. Operator-run work stations are rapidly being replaced by computer-operated ones. Subcontracting has become an essential partner to assembly operations. Marketing and business strategies have become at least as important as design of product. And advertising has become an essential tool for assuring the public that the products in question are the best, the cutting edge, the state of the art, and even the most patriotic purchase. This has become an astoundingly sophisticated, complex and highly competitive business.

Whether you are a fan of individual lutherie or commercial/ factory production, these are the two main legs, so to speak, on which contemporary American guitarmaking stands. They are also the frame of reference for the writing of these articles. And, in order to bring this frame into better focus, I want to sketch out its beginings.

Origins of the Classical Guitar

The classical guitar is the first modern guitar. It is European in origin and it supplanted the earlier vihuelas, Baroque guitars, lutes, guitarras batentes and citterns to become the dominant portable stringed instrument of its time. Its body shape has been more or less universally agreed on for some l50 years, with rather little variation from one maker’s design to another apart from minor differences in size, internal bracing layout and the signature shape of each maker’s peghead.

The standardization of parameters for the modern guitar came into being with the work of Antonio de Torres around 1850, ending a period of extraordinary experimentation and diversity of design which followed the disappearance from use of the earlier fretted instruments. This quest for a more satisfactory musical instrument occurred within the context of a general European cultural expansion in music and musical entertainments, which was itself created by the social and political changes that gave rise to a new European middle class — a class with sufficient resources of disposable time and money with which to cultivate a taste for the various arts. If the design of the modern guitar was crystallized in the work of Antonio de Torres, it was then cast in concrete by the work and influence of Maestro Andres Segovia between l890 and l950. Segovia took an instrument which was considered a folk instrument at best, and virtually singlehandedly made it serious and respectable the world over. The students he taught, and in turn their students, are the leaders of the world of the classical guitar today. In their playing, in their teaching, in their promotion of proper playing technique, and in their position of moral authority these individuals have, together with the luthiers who made their instruments, defined what the classical guitar can do, needs to be, and is. I must add that everything said here about the classical guitar applies to flamenco guitars as well. Even though these instruments are played in distinctly different musical networks, there is evidence that there was no meaningful distinction made between “classical” and “flamenco” guitars, by either the makers or even most musicians, until the 1950s.

Classical and flamenco guitars originated within a tradition of hand craftsmanship of stringed instruments. This is not so much because hand craftsmanship is inherently superior, as that the roots of European lutherie predate the industrial revolution and its relentless mechanization of all modes of production. Hand craftsmanship was the only option for a long time. This is not a bad thing, because the level of skill brought to lutherie was unbelievable — as a visit to any museum with a good collection of historical string instruments will show. And, because this kind of lutherie was associated with real individuals, a tradition has been created whereby modern classical guitarmakers are the inheritors of some past heroes to look up to and whose work they can emulate. These revered icons, cousins to the illustrious icons of violinmaking (Amati, Stradivarius, etc.), are people like Antonio Torres, Hermann Hauser, Luis Panormo, the Fletas, the Ramirezes, Simplicio, Santos Hernandez and other historical European makers. Modern classical luthiers like to think of themselves as walking in these pioneers’ footsteps, or at least following the path that they traveled. None of this has stopped classical guitars from being produced in great numbers in factory settings; but the basic design has changed only minimally because the acceptability of this guitar’s design is still rooted in the traditional look, and traditional expectations still attach to it. The name of the game in contemporary classic guitar lutherie is adherence to and refinement of — rather than experimentation with or departure from — traditional design. Anyone who has ever gone into a classical guitar store will have been struck by the fact that, besides differences of coloration of their woods and minor details of design, these instruments all look remarkably alike. There are exceptions to this, of course, but as a rule it is the rare classical guitar maker who can make substantive changes in traditional design, and survive. This inflexibility of design does not apply, however, to the steel string guitar: quite the opposite, actually.

Classical and flamenco guitars originated within a tradition of hand craftsmanship of stringed instruments. This is not so much because hand craftsmanship is inherently superior, as that the roots of European lutherie predate the industrial revolution and its relentless mechanization of all modes of production. Hand craftsmanship was the only option for a long time. This is not a bad thing, because the level of skill brought to lutherie was unbelievable — as a visit to any museum with a good collection of historical string instruments will show. And, because this kind of lutherie was associated with real individuals, a tradition has been created whereby modern classical guitarmakers are the inheritors of some past heroes to look up to and whose work they can emulate. These revered icons, cousins to the illustrious icons of violinmaking (Amati, Stradivarius, etc.), are people like Antonio Torres, Hermann Hauser, Luis Panormo, the Fletas, the Ramirezes, Simplicio, Santos Hernandez and other historical European makers. Modern classical luthiers like to think of themselves as walking in these pioneers’ footsteps, or at least following the path that they traveled. None of this has stopped classical guitars from being produced in great numbers in factory settings; but the basic design has changed only minimally because the acceptability of this guitar’s design is still rooted in the traditional look, and traditional expectations still attach to it. The name of the game in contemporary classic guitar lutherie is adherence to and refinement of — rather than experimentation with or departure from — traditional design. Anyone who has ever gone into a classical guitar store will have been struck by the fact that, besides differences of coloration of their woods and minor details of design, these instruments all look remarkably alike. There are exceptions to this, of course, but as a rule it is the rare classical guitar maker who can make substantive changes in traditional design, and survive. This inflexibility of design does not apply, however, to the steel string guitar: quite the opposite, actually.

Origins of the Modern Steel String Guitar

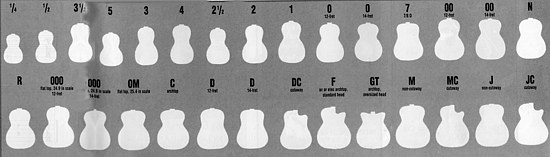

Steel string guitars, unlike classicals, do not come to us from a tradition of handmaking. Also, unlike classicals, steel string guitars come in many shapes and sizes and seem to thrive on variety. There are dreadnoughts, jumbos, weird little travel guitars, concert models, parlor guitars, orchestra models, twelve and fourteen fret neck guitars, cutaways, bowlbacks and flatbacks, flat tops and arch tops, multiple neck instruments, electrified models, six stringed and twelve stringed and drone stringed guitars, fanned-fret and taper-bodied and bubble-top guitars, space-age plastic guitars, etc — not to mention the explosion of ornamental decoration and inlay which is the current rage, and, finally but not least, shapes or designs which are associated with a specific maker like Steve Klein, Larry Breedlove, Stefan Sobell, George Lowden, Jeff Traugott, myself and others. This list, moreover, is bound to expand. This plentitude is shaped by some important factors.

The steel string guitar is an American instrument, not European. It is much more a child of the mass market and technology than it is of tradition. Because of this, it is short on heroes, pioneers, or personal models. The first steel stringed guitars were made in this country by Old World trained violin and guitar makers who quickly went to small factory production in response to the needs of the American market — which were for plentiful, cheap, and easy-to-hear folk, parlor and band instruments. The godfathers of the steel string guitar aren’t seen as having established American lutherie; those whose names we remember today, such as Martin and Gibson, aimed at and achieved production, which is a different thing altogether. In fact, production became the model, and factories were for many decades the only sources of steel string guitars. Individual American lutherie in the craftsman tradition — with the exception of the Larson brothers and later John D’Angelico — did not flourish. In consequence, the contemporary steel string guitar maker has been deprived of a personal link to the past and must either identify with a largely factory/production tradition, or claim independence from tradition and sort of give birth to himself. There is now, finally, a small core of very talented contemporary steel string luthiers who serve as models for others. But, significantly, they’re all of the postwar generation and most of them are still alive. It’s not the same as having pioneer models from a hundred and fifty years ago.

In terms of having an individual musical identity of its own, the flat-top steel string guitar only began to be taken as a serious instrument some forty years ago, about the time when white society at large embraced the folk music movement. Before that, the guitar had an oddly divided life. In mainstream culture it was used largely in a parlor setting or as a folk, rhythm, band and accompanying instrument. In fringe society, on the other hand, jazz players like Django Reinhardt, Charlie Christian, Lonnie Johnson and Eddie Lang brought the guitar to life with an energy and musicality that was astoundingly original, and Delta blues players like Mississippi John Hurt, Robert Johnson and Big Bill Broonzy played soulful and evocative music of heartstopping expressiveness. But, outside its use in jazz and blues, there was no solo guitar to speak of until the 1950s. There wasn’t even a body of music specific to the guitar until relatively recently; most songs played or accompanied have been folk, traditional or popular melodies or fiddle tunes adapted to the guitar, or orchestral arrangements. The folk music culture of the sixties brought into public consciousness the Mississippi Delta blues stylists and singers who would otherwise now be forgotten but who strongly influenced a new generation of players, singers and music. Individuals like Hank Snow and Merle Travis pioneered the playing of actual melodies on the steel string guitar; this was subsequently refined wonderfully in the music of Chet Atkins. Doc Watson, within our lifetime, became the first serious steel string guitarist the world knew — and remained the only one for about ten years. He was joined by players like Clarence White, Tony Rice and Dan Crary, who became seminal influences in opening up the musical possibilities of flatpicked steel string guitar — and John Fahey and Leo Kottke, who are the initiators of the continually growing fingerpicking idiom which presently includes players such as Alex de Grassi, Chris Proctor, Peppino D’Agostino, Duck Baker, Peter Finger, Ed Gerhard, Martin Simpson, Don Ross, Pat Donohue, Doyle Dykes, Michael Hedges, Jacques Stotzem, Pierre Bensusan, John Renbourn, Bola Sete, Shun Komatsubara, Tim Sparks, and many, many others. This music is enriched by its receptivity to and inclusion of elements of folk, ethnic, ragtime, Celtic-Irish, jazz, blues, Latin, Caribbean, African, and classical music — and those instrumentalists such as Larry Coryell, Tim Sparks and Steve Hancoff who are transcribing for the guitar from orchestral and pianistic influences must also be acknowleged.

I mustn’t forget to include mention of the popularization of Hawaiian slack-key music through the efforts of musicians such as Keola Beamer, George Winston and Raymond Kane. And then, there’s the slide guitar. The list is long. Nonetheless, it is most important to note, with regard to the history of the modern steel string guitar, that it is so new that many of the very important people in its musical development are still alive (just like the postwar guitarmakers) and their music freely obtainable. I should also mention, finally, the phenomenally widespread and significant growth in this generation of the electric guitar, its music and its players — although this is a subject so far outside the scope of this article that its adherents have not only their own separate demographics, culture, magazines, icons, discography, books and publications, but clothing as well. All in all, the steel string guitar has had a long gestation period in which to soak up many complex and varied musical influences, strains and flavors — in exactly the same way the classical guitar simmered between about 1730 (the end of the dominance of the lute) and 1850. I think such simmering is a very good thing, and I’ll address some of the things this has led to in the next installment of this series.

(reprinted from Fingerstyle Guitar, #40, 2000)