September, 2013

Glue. All woodworkers use it. And what can one say about it that hasn’t been said already? — that is, aside from jokes like “My wife gave me a book titled The Complete History of Glue for my birthday. What was it like? Heck, once I picked it up I couldn’t put it down…”

Well, the principal function of any glue — outside of considerations of working time, adhesive strength, and materials compatibility — is simply to enable one surface to stick to another. Period. Therefore if the glue has been appropriately selected for the task at hand and applied correctly, all glues work satisfactorily: the glued parts all adhere together for a long time without bleeding, creeping, breaking down, discoloring the woods, or otherwise failing.

For woodworkers in general, hide glue and fish glue were the only glues available for a long time. More recently, synthetic and chemical glues have been developed which are more convenient to use, give extended working time, are waterproof, etc. For the general woodworker who is not committed to using epoxies and such for specialized purposes, Titebond (and the other aliphatic resin glues which are sold under a variety of names) pretty much heads the list of modern favorites. It works every time. The somewhat less convenient hide glue (made from animal hides and hooves) is still used by purists, craftsmen, and traditionalists. It works every time as well. Elmer’s White glue, that staple of school projects, is a polyvinyl glue which never gets really hard; hence most woodworkers don’t use it on serious projects.

The Titebonds and hide glues are certainly the favorite adhesives when it comes to making guitars despite the latter’s minor inconveniences of preparation and quick setting time. On the whole they give equivalent results, but with one significant difference. This is most noticeable to repairmen and restorers — those whose work requires them to take glue joints apart, or to deal with failed joints. The difference is that of destructive vs. non-destructive reversibility. What that means is that one can take a hide glue joint apart (if one knows how, and if one is willing to be patient) without removing of any actual wood. One cannot take a Titebonded joint apart without losing at least a little bit of the original wood: one undoes the joint and then needs to do some sanding or scraping to expose fresh wood. This might not seem like an important consideration in most woodworking, and it is pretty much irrelevant in factory-made guitars: there’s enough wood in these so that you can lose 1/64″ of thickness and still be all right. But in craftsman-level guitar work, which can allow for more carefully titrated and thicknessed parts, the loss of a few thousandths of an inch of wood may make a difference in sound.

There’s also a second consideration when it comes to doing repair and restoration work on a valuable collector’s instrument. In this realm, having the instrument be as fully original as possible is desirable: alterations and modifications of any kind can devalue the instrument. So, in these cases, it is preferable to find that the guitar has been held together with hide glue: the parts can be taken apart and reglued while maintaining fidelity to the original sizes, thicknesses, and specifications of the woods, not to mention the original intent and methodology of the maker. One can understand that a damaged Louis XIV chair that’s been epoxied together wouldn’t be considered authentic — and it would be priced accordingly.

I’d always assumed that Titebond was water soluble (after all, it dilutes easily with water when it’s still liquid) and that it could be removed completely, after it had hardened, if one wanted to spend enough time sponging and wiping it carefully away with warm water. It’s exactly what one can do with hide glue. But Titebond is a synthetic glue, not an organic one, and it has unexpected staying power. I should add that with both of these glues one heats a joint that is to be undone, so as to soften the glue and help it release its hold.

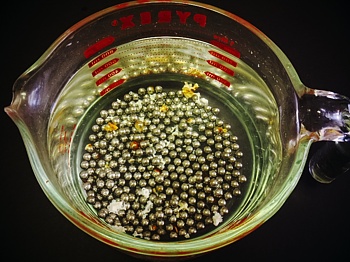

Titebond is only partially un-doable. This property of it impressed itself on me in an interesting and accidental way. I’d made a pencil holder a long time ago by pouring some Titebond into the bottom of a recycled plastic jar that had a rounded bottom edge and then dropping a bunch of ball bearings in for ballast — to ensure that it was heavy and stable enough to not tip over once I filled it with pencils and pens. The Titebond soon hardened and rendered the ball-bearing ballast permanent, and the jar held my pencils and pens nicely. Some years later I was able to afford a real pencil holder, so I transferred the pens and pencils and filled the old jar with hot water so as to melt the Titebond and reclaim the ball bearings. I thought it would take a few days of soaking for the Titebond to give way; the ball bearings were stainless steel and wouldn’t rust.

Titebond is only partially un-doable. This property of it impressed itself on me in an interesting and accidental way. I’d made a pencil holder a long time ago by pouring some Titebond into the bottom of a recycled plastic jar that had a rounded bottom edge and then dropping a bunch of ball bearings in for ballast — to ensure that it was heavy and stable enough to not tip over once I filled it with pencils and pens. The Titebond soon hardened and rendered the ball-bearing ballast permanent, and the jar held my pencils and pens nicely. Some years later I was able to afford a real pencil holder, so I transferred the pens and pencils and filled the old jar with hot water so as to melt the Titebond and reclaim the ball bearings. I thought it would take a few days of soaking for the Titebond to give way; the ball bearings were stainless steel and wouldn’t rust.

Well, to my surprise, the Titebond did soften but it didn’t dissolve at all; it was still there after three weeks of continual immersion in warmed water. It softened enough that I could squeeze the ball bearings back out, but what remained was a honeycombed, spongelike mass of rubbery aliphatic resin that looked like a coral reef — and that hardened up rock solid again as soon as it dried out. (See the accompanying photos.)

As it turns out, it’s not only the composition of the glue that makes the problem for repairmen and restorers. It also has to do with how the adhesive achieves its results. In the case of the newer glues such as Titebond, these grab onto the materials they come into contact with by means of penetrative adhesion: they sink into wood fibers and grab hold. And once there, they want to stay. The upshot is that undoing such a joint usually results in some splintering, tearing, or pulling up of wood fibers, and thus leaving a rough surface that will itself need to be smoothed before any regluing can occur.

As it turns out, it’s not only the composition of the glue that makes the problem for repairmen and restorers. It also has to do with how the adhesive achieves its results. In the case of the newer glues such as Titebond, these grab onto the materials they come into contact with by means of penetrative adhesion: they sink into wood fibers and grab hold. And once there, they want to stay. The upshot is that undoing such a joint usually results in some splintering, tearing, or pulling up of wood fibers, and thus leaving a rough surface that will itself need to be smoothed before any regluing can occur.

In addition, whether or not there’s been pulling away of wood fibers, some of the Titebond will remain on the wood surface and, as I pointed out with my ball-bearings experience, Titebond will not simply wash away. Thus the usual way of post-Titebond surface preparation is to sand or scrape at the roughened sections (imagine trying to sand or scrape cold honey off a piece of plywood; it’s the same thing) until smooth wood is reached; then, one reglues.

Hide glue, on the other hand, achieves its results by molecular bonding. Titebond won’t hold very well onto something it cannot penetrate, such as glass. But hide glue will. In fact, it’ll hold on like a barnacle on a ship’s hull. In the old days before sand blasting, glass was decorated by covering the to-be-textured-or-highlighted area with hide glue; once this dried the hide glue was chipped off with a chisel and a hammer — and it would take some of the glass with it. The contrast between this newly chipped surface and the smooth original surface of the glass is how lettering and decoration in that medium used to be achieved! The really interesting part of this is that, molecular bonding aside, one can wash hide glue completely away without affecting the surface it has been applied to. Like campers, hikers, or guests with an ecological consciousness, hide glue can disappear without leaving any trace or litter behind it.